How to make your spirits bright by

transforming yourself into an abominable snow-bicycler

by Keith Couture

Winter bicycling? You must be crazy!

This is the most common reaction

I receive upon telling someone of the joys of winter biking. I

empathize with the viewpoint, I really do. But I'd like to offer two

rhetorical counterpoints to this incredulity.

There

was a time in my life and likely in many of our readers' lives

(although I won't make the mistake of saying this is universal) when

upon waking up to see a lawn and a city blanketed in white fluff, we

jumped joyously out of bed, skipped breakfast, put on our warmest

boots, mittens, and coat, and went out to play in the snow and cold.

We would stay out for hours

and we'd only come in when we saw through the kitchen window that hot

cocoa was being served up. What happened to that joy?

The second

counterpoint is more of a personal anecdote. When I was in high

school I rode my bike to school occasionally. I was young and the

ideological reasons to refuse the car and choose the bike had not yet

established themselves. So I was a frequent, but not dedicated,

bicycler. The irony is that I specifically chose to ride on days when

the weather was extreme. Why did I do this? Looking back, I believe

it was because I was still a kid, and as such, still child-like in my

pursuit of the adventure of winter. I wanted to play in the snow.

Having reflected

on the latter notions for some years now, I can identify the

motivation behind my dedication to biking in the harsh winter months.

It was the adventure. I believe that embracing the fun and adventure

of winter bicycling is tantamount to the practical preparations

needed to embark on this “crazy” endeavor. It seems we are all

taught to forget that playtime in the snow that we used to crave.

Winter bicycling is our way to get it back.

If you can muster

your inner child to ride in the winter you are halfway there. The

other half of the battle is preparing yourself practically. Read on!

Clothes:

One of the most

common reasons for reluctance to ride in the winter is the cold.

Funny, because it didn't seem to stop us when we were kids. Granted,

as kids we weighed about fifty pounds, our vascular system was

robust, plus we didn't sweat and have to look professional. But these

things can be addressed and they don't need to be overcomplicated.

Cotton is typically a bad idea for the layer next to your skin

because sweat (and you will sweat) gets absorbed by it and it doesn't

evaporate all that well. Merino wool and synthetics are a good choice

for this first layer. After that, you'll need to be the judge of what

will keep your warm. Is it windy? A windbreaker is a good idea for an

outermost layer. Windy and rainy? A waterproof windbreaker then.

Layers are good and so are zippers. Getting too hot is common in the

winter and it's nice to be able to unzip in a few spots.

Figure 1a

A synthetic base layer, a heavy hoodie, a wool or down vest if it's really cold, and a windbreaker make a great combination.

Gloves are a must

(how else will you throw snowballs at deserving motorists?!), but

often-times I hear bike-industry people overstate the importance of

dexterity. If mittens will keep you warmer and you can still operate

your brakes, maybe they're the better choice. Remember, if you're

miserable out there, you're never going to want to do it again, even

if you can shift with rapid-fire quickness!

Headwear is also a

must depending on your climate. If you live where it's rainy then

maybe just a waterproof hood will suffice. But if you live in the

upper Midwest then a serious balaclava/scarf and wool hat combo is a

good way to go. If you prefer to wear a helmet and can't fit it all

underneath, that's okay. Most balaclavas that are out there are thin

enough that you can wear your helmet on top of one. A helmet will do

an okay job of keeping your head warm (depending on the helmet), and

furthermore, you can get a helmet cover to do a little bit

more—especially to keep the wind and rain out.

Figure 1b

A balaclava and a hat, or a helmet with helmet cover. A beard seems to work, too.

Shoes.

Definitely wear those. A lot of people in the cycling community will

try to convince you that clipless pedals and the corresponding shoes

are the way to go. I contradict this. For the average rider it's

probably best to just have normal, flat pedals on your bike, ones

that are big enough to fit a large shoe like a snow boot. You should

be able to comfortably wear a shoe that is going to keep you warm

enough. Secondarily, not having your feet clipped in to your pedals

in the winter will give you the ability to catch yourself should you

feel the bike sliding on ice and about to go out from under you. If

that happens, don't worry: ADVENTURE! You're likely to fall a few

times, but those falls will help you develop the type of control and

balance that are unique to winter riding.

Pants,

well, I will say you should probably wear those, even though I don't,

but this is because I am truly masochistic when it comes to winter

apparel. The pants you wear need not be synthetic unless you expect

to get wet, in which case, it may also make sense to wear some

waterproof wind-pants on top of whatever you choose to wear. If it's

snowy, but not currently snowing or raining, wear whatever you would

normally wear if you were going to bike on a chillier day. I like to

do the “Huck Finn” (figure 1c) occasionally; jeans rolled up to

just below the knee. You don't have to roll them up that high, and

you could pair it with some high socks, so no skin is exposed.

Figure 1c

The "Huck Finn" and some knee-socks. Yes, your calves will become that big if you bike in the winter.

Bike Clothes:

Depending

on how your bike is dressed, you may not need as many layers

yourself. For instance, fenders can make or break a ride—especially

to work. In the rain, they prevent a cold, wet stripe from being

Jackson Pollocked on your back, and in the snow they keep the same

off your back with the added benefit of keeping your drivetrain and

shift cables a lot cleaner. When it's snowy and cold outside, your

cables may have a tendency to get snow caked on them, which can

disrupt shifting. This is assuming your bike uses derailleurs and

does not have an internal gear hub (see my previous article on

Internal Gear Hubs for more info!).

If at

all possible, store your bike indoors during the winter (if at all

possible, store your bike indoors always!

But in this particular case, when you're going to work let's say,

eight hours of exposure to the elements can be harsh. If there's any

way at all to blackmail a boss or some coworkers into getting some

enclosed space to put your bike, by all means, get out the ransom

letters). If your bike does have to sit outside when it's snowing all

day long while you're at work, you may have to give your bike a good

bounce or two and maybe scrape off some snow and ice from the cables

(they often run down the underside of the downtube), and derailleurs.

See if you can do that faster than your coworker scraping his or her

car's windshield.

The bicycle's

shoes are its tires, and in the winter they are definitely an area

that needs attention. I'm about to use some seriously technical terms

like “greasy snow” and “bobsled snow” so try to keep up.

There are some conflicting hypotheses about what tires to use in the

winter. Most of them have merit, but the problem is that some of

these arguments are purely situational. For instance, studded tires.

These babies can set you back around $100 for just a single tire!

Some people advocate for them. I would advocate for them on a limited

basis.

Studded tires are

most appropriate for: people who live in Minnesota, probably

Wisconsin, northern Michigan, the Dakotas, upper Great Lakes region,

and northern New England and some other places, too, maybe. I don't

know, I've never been there. But here's why: if you live in a place

where snow falls, it stays cold, snow isn't plowed (or isn't plowed

completely, or, let's face it, not in any timely manner), then snow

gets packed down, that snow then turns into Bobsled Snow, or even

ice. Bobsled Snow isn't clear like ice, but its surface is ice and is

very slick. Even worse, Bobsled Snow has become packed down into

shallow divots and canyons (maybe one to two inches deep), which I

call Bobsled Runs. These runs can pose serious issues because your

tires will naturally slide into the low parts and this can really

endanger you if you need to maneuver. If you find yourself riding on

the high part of a tiny ice canyon (see figure 2a), it's basically

like riding a knife-edge. At any moment, your tire could slide

laterally into a divot, giving you little time to react and you could

be headed for Wrist-Cast City. These conditions can be navigated with

much greater ease with studded tires. The metal studs pierce the ice

and give you traction so that there is little to no lateral sliding.

You won't fishtail either, which is good.

Figure 2a

Viewed from the front, a tire riding on ice or hard-packed snow

To

contrast, I currently live in Denver where it snows fairly large

amounts, but due to weird, rain-shadowy things, the weather is

frequently mild and the snow thaws and melts within a few days to a

week after. There is very little snow-pack, ergo very little Bobsled

Snow. In fact, in the winter, there are more days of riding on bare

pavement than not. In these conditions, studded tires might be $200

poorly spent because the metal studs would wear themselves down on

the concrete, significantly reducing the life span of the tires.

There

are some who advocate strongly for skinnier tires in the winter. They

say that a narrow tire will cut through the snow and make contact

with the pavement underneath, giving you good traction. This is

certainly true. Skinnier tires are the perfect antidote to what I

call “Greasy Snow.” Greasy Snow happens when it's been snowing

for a day (maybe it started in the early morning or the previous

night) and it stopped that late afternoon or evening. Car traffic has

smushed some of it down, but there are still high patches left here

or there.

The

high patches are the Greasy Snow. I call it Greasy because there are

really two kinds of snow interacting. The snow underneath the high

patch has been packed down from car traffic, and is actually fairly

tacky to a tire, but on top of it is new snowfall that has not been

packed down and may be fairly thick. The snow underneath might be

tacky to a tire, but the snow on top of it will slide over it with

ease when pressure is put on it, say, by a front tire; almost like

the unsuspecting shoe of a pedestrian stepping on a banana peel. As

the front tire comes down, it smushes the patch of snow down flat,

but this snow slides right on top of the packed snow on which it is

resting, which causes your front tire to float and slide in various,

unsafe directions laterally. See figure 2c for clarification.

Figure 2c

The "Greasy Snow" and the packed snow are distinct surfaces and slide against each other

Thinner

tires (specifically thin, yet knobby tires) cut through the high

patch of Greasy Snow and make contact with the packed snow

underneath. Instead of floating on top, they penetrate through and

displace the snow that is so Greasy and dangerous. However, if you

were to run these tires over some Bobsled Snow, you'd be a in a rough

place. If you can count on Greasy Snow conditions in your city, maybe

having a bike with thinner, knobby tires makes sense. However, there

are some climates that cause not one but all of the aforementioned

conditions. For us, a tire is needed that can manage adequately on

any given day: Greasy, Bobsled, Ice, Dry, or otherwise. How do you

choose a tire that is going to give you the best option for a wide

variety of conditions?

I

think the key is to switch to tires that are larger (wider), knobby,

and run at a lower pressure than normal. The Achilles Heel of this

combination is going to be thick patches of Greasy Snow. But a major

facet of surviving the dreaded Greasy Snow is just to avoid it in the

first place. Stick to where the snow is packed down and you won't put

yourself at risk. The larger tires naturally have a bigger contact

patch (the surface area of a tire that is actually touching the

ground). When tires are run at a lower pressure (say 35 or 40 psi),

they squish down even further, making the contact patch even larger.

The knobs on the tire's tread and sides also make contact and fill in

terrain that isn't truly flat such as Bobsled Snow (see figure 2c)

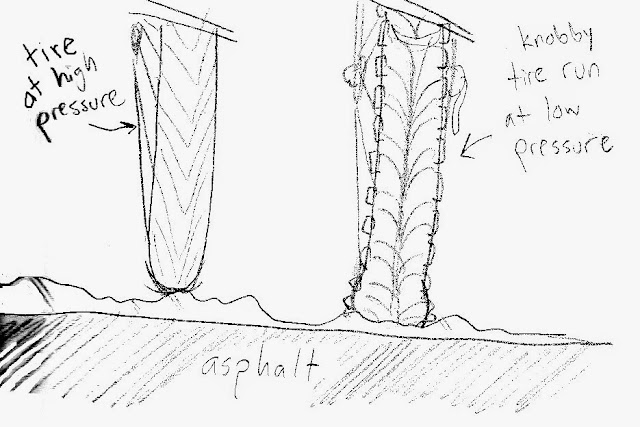

Figure 2c

A normal tire at high pressure will not have as many points of contact as a knobby tire at lower pressure

Lastly, if you

experiment with these options and nothing seems to work for you, all

is not lost! There is a company called SlipNot Bicycle Traction that

manufactures bicycle tire chains (or you can make your own chains

http://icebike.org/Equipment/tirechains.htm). The nice feature about

them is that they are removable, so you only need to put them on as

needed.

Steeling Yourself:

The

most difficult aspect of winter biking, however, is the mental

preparation. The analog would be going jogging in the morning. The

jog itself is not as difficult as getting out of bed and making

yourself do it. It is the same with biking, or arguably, making any

significant change to your lifestyle (eating vegetarian, cutting back

on facebook/twitter/etc, or trying to write left-handed—although

why you'd want to do that last one I do not know). The idea that you

are forcing yourself out of your cozy bed even earlier

than you normally would be in order to go to work not

in your cozy car with its selected going-to-work playlist, but on

your bicycle, which will force your muscles to do work out in the

cold, dark, snowing, possibly sleeting world out there is a powerful

idea. It's the kind of powerful that you'll need to fight. It is

powerful because the idea

of having to bicycle in the winter is actually more dangerous to your

attempts to make yourself into a winter biker than winter biking

itself is. The perception of that discomfort is more uncomfortable

than it actually is to be outside on your bicycle in the winter; that

is what makes it so easy to succumb to the car.

Now comes the part

you don't want to hear: there really is no shortcut to this. You have

to steel yourself, move yourself, and make yourself do it out of

sheer willpower. There's no mental fender that keeps you dry from the

idea of what cold and wet feel like. There's no metal studded tire of

the mind that can help you from slipping back to sleep after hitting

the snooze. You just have to do it. The good news is, there are

plenty of people who do it in hundreds of cities, and there is

nothing special about us. Which is to say, we are not superheroes and

we don't possess some gene that makes it easier for us to bike in the

winter. We're just normal humans who've made it a habit to do this,

which means you can do it, too.

If I could offer

one piece of advice that might help you, it is this: connect with

your inner kid. Would your inner kid be stopped because you realized

you'd have to get wet and cold as you built a snowman? Probably not.

Would your inner kid hit the snooze again if they saw the

snow-covered lawn? Knowing full-well what snowball fights awaited? No

way, Jose! So, when that alarm rings, it's dark out, and your bike

beckons, don't groan and roll over, instead pretend your big sister

just hit you with a snowball. Go get retribution! The adventure

awaits.

Photos property of Keith Couture